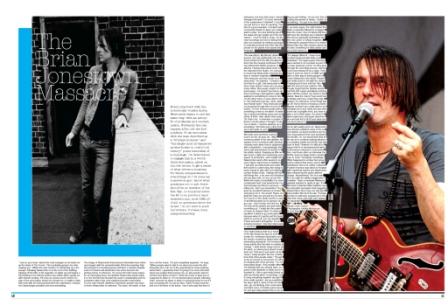

The Brian Jonestown Massacre - The Beat Happening (2008)

Every interview with the notoriously volatile Anton Newcombe seems to end the same way: with an abrupt fit of profanity and condemnation. Evidently this can happen after just the first question. So an encounter with the man described as a “brilliant monster” and “the single most ill-tempered motherfucker in rock’n’roll history” poses somewhat of a challenge.

I’m determined to engage him in a worthwhile discussion, albeit on his own terms, to get a sense of what drives a musician for whom independence is everything. So I’ve done my homework and I know what questions not to ask: there should be no mention of the film Dig!, no inquiries about the 60 or so previous band members and, most difficult of all, no questions about the music. I’m not here to push his buttons: it’s been done…comprehensively.

“Just so you know,” warns the road manager as he leads me up the stairs of The Forum. “He’s probably going to be interviewing you.” Within the next minute I’m clambering up a fire escape, following Newcombe on to the roof of the building. Ripping off the filter of his cigarette, he lights up and begins a free-flowing if not entirely random pre-amble while eyeing me with intense scrutiny.

Yet even as I press record, there’s no sign of the provocative streak he’s known for, no battle of wits that ends with me being steamrolled into submission. Instead he’s disarmingly amicable and accommodating.

The image of Newcombe that previous interviews have relied upon began with the unmentionable 2004 documentary Dig! Its portrayal of a troubled genius hell-bent on artistic integrity even if it means self-destruction has since become the primary frame of reference. Of course the truth rarely makes for an interesting story, but whether Newcombe would admit it or not, the film has boosted his career considerably and his contention with it has only sustained people’s fascination.

For the man himself, whatever impression people may have of Anton Newcombe is irrelevant. The point, he insists, is that he is not the music. “It’s just completely separate,” he says. “When people want to talk to me about my music the first thing they do is rob me of the opportunity to know anything about them. I guarantee that I’m going to be more informed about any subject that involves me, so why would I want to sit there and listen to them? I think the music is what you’re supposed to listen to. I’m not worried about people criticising how I execute my ideas or what I’m doing because for me it’s just conceptual art; it’s just an idea.

“Pablo Picasso beat the shit out of all three of his wives. I don’t advocate that kind of behaviour, but does that mean I should disregard his work? I’m more interested in the suspension of disbelief. If you can get lost in it, then it’s working. Theatre is a good example. Compare bad community theatre to when you really watch a play. You stop thinking about the stage and get caught up in the narratives – I look for that in music. So the new recordings are kind of taking the piss out of people by making up songs in Icelandic because less than 300,000 people on the planet even speak the language.”

The new album, My Bloody Underground, not only synthesises the influences hinted at in the title but absorbs them into the musical continuum that has defined the BJM’s previous 12 albums. Having improvised much of the material in the studio, I’m curious to know how Newcombe channels the flow of creative inspiration.

“Not everyone can hear music on a deep level,” he explains. “I know for a fact that it’s a gift. Just being able to hear music doesn’t mean you can play music either. But people create it in different ways. I’ve heard Paul Simon sits there bouncing a ball against a wall, waiting for something to come to him. On the other hand, a muse didn’t come to The Darkness and say: ‘yeah, spandex! Karate kicks!’ They obviously set out by going through their record collection. I’m one of these people where something comes to me when I’m walking or doing something active and suddenly I’ll think: ‘wait, what’s that song? Oh, that’s me’. I remember a couple of times in my life where I thought: ‘fuck! I’ve no ideas. I must be washed up or something’. But that’s just a dirty trick your brain pulls on you.”

Moments such as these must be scarce for the 40-year old. With enormous belief in his own abilities, he speaks of his convictions with absolute certainty even when they’re peppered with contradiction. Unsurprisingly, that same self-assuredness is intrinsic to his artistic output. Sleeping as little as two hours a night and overseeing every aspect of production, each insight into Newcombe’s work ethic seems to reveal a figure impervious to limitation.

“I just pick up instruments and make them work in a weird way, like trying to teach myself to play sitar and making up fake Indian music. I always tell myself things like: ‘a six year-old Ukrainian girl can play cello, so you can do this’ – within the realm of possibility! For more complicated stuff I just pretend like I’ve had amnesia and there’s someone telling me: ‘don’t you remember? You were an excellent batsman at cricket’ and just go for it. You know? Figure out what the rules are and just try my best.

“So if you’re in the studio and it’s a case of wondering what you’re going to do, you say: ‘I don’t know, let’s find out. De-tune all the guitars and just make something up’. I really like the power of music to redeem itself. It’s interesting when it starts to go some place because when it’s spotty and the band starts to sound off, you can wrestle it back and pull it all together. It’s an amazing moment. I like that rollercoaster element.”

One might conclude that it’s a result of the two things the band is most known for: excessive intoxication and the tension created by Newcombe’s demanding standards. The frontman freely admits that the latter is unlikely to change: “I write whole songs and do all the work, so [democracy] doesn’t really work out. That won’t ever work out because I really wouldn’t like the contributions that other people make.”

Though as far as excess is concerned, it’s often an integral part of the process. “I’m not advocating drugs. They amplify different feelings that you already have, so I guess it just depends on what you’re interested in. I like to get really fucked up with my friends when I’m working. I try to bring everything together and get it done really quickly. I set up everything the way I want it, work for like 30 minutes, go out drinking, then come back and drink more. It’s better just to have fun and get really wasted than to be sitting around fretting: ‘oh my God, this is costing thousands of dollars, I better do something’. You get more done.”

If, as some argue, the myth behind the Brian Jonestown Massacre is bigger than the music, then it’s likely that time will have the deciding say in whether the band is gradually assimilated into the rock canon or simply forgotten. Entering the popular lexicon is a desire Newcombe has often spoken about but it’s also something he feels artists can’t put a time frame on.

“It’s always different. I mean look at what happened with Belle and Sebastian. The legend goes that they were elected to do a project as part of a music business course. So they went through the recording process, did the cover and released it as a class. Then bam! It sold out, they’re in NME and well on their way to being played in every Starbucks in the world. People just really loved it. But with the Velvet Underground it took until the ’90s; with the Doors it took until the ’80s.

“People forget that the Beatles would sell 300,000 copies worldwide and they were still the number one band on the planet. Now the Crazy Frog record has probably sold more copies than Sgt. Pepper’s. It’s ridiculous; some things just go off. But [in terms of leaving a mark] I figured out that if you really want to accomplish all of your ideas and see them come into a tangible form, you have to give a lot of them away. You have to work really hard, let people steal from you and just let it roll off your back and not worry about it.”

As he will readily point out, Newcombe has already outlasted many of the record labels, ex-band members and former drug partners that once predicted his demise. So one would think that all he can do is continue making albums of a consistent quality and let the rest take care of itself. However, it’s difficult to argue that he is misrepresented when controversy continues to surrounds him.

Just hours after our interview, the BJM’s usual on-stage friction carried over to some “horseplay” backstage. What happened is unclear but venue policy required that police and an ambulance had to be called. Guitarist Frankie Emerson was taken to hospital with superficial injuries and Newcombe was released by the police without charge.

Nevertheless The Sun saw fit to run with the wildly exaggerated headline: “Brian Jonestown Massacre guitarist stabbed to death at gig.” It’s this kind of distorted filter between reality and public perception that suggests Newcombe’s story may one day warrant another film all of its own. Perhaps by then he will have acquiesced to the idea that music and myth can’t always be separated.